Ordnance Survey’s Andy Wilson and Mark Tabor explain how they used cutting-edge technologies to automate the mapping of Lusaka – from headquarters in the UK

It’s been 11 years since Zambia last conducted a census.

The most recent one, completed in 2010, recorded demographic data on 13 million people and 3.2 million households – missing an estimated 7.3 percent of the population.

These unaccounted-for people were mostly from rural areas — but a lot has changed over the past 11 years. Many rural dwellers have headed to the cities to find jobs, and not just in Zambia.

All over the world, urban economies are buoyed by an influx of new residents hungry to work and live. In developing nations like Zambia however, this occurrence is happening at faster rates – with local government services unable to meet rising demands for housing, healthcare, and even clean water.

The local government is looking to improve on its 2010 results as it conducts its latest census, delayed by a year due to the pandemic.

And to improve its data pool, it sought the help of one of the oldest mapping agencies in the world – Ordnance Survey. The UK’s national mapping agency was brought in following talks with the International Growth Center and the Commonwealth Association for Architects, to provide a detailed look at the slums of Lusaka, the country’s capital.

Ordnance Survey's Andy Wilson and Mark Tabor spoke with AI Business to explain how they used cutting-edge technologies to automate the mapping of the city, and how this process could be applied to several other use cases around the globe.

Capturing and configuring

The Ministry of Local Government sought to address gaps in local services given increases in pressures on public services in Lusaka, the pair explained.

They noted that around 70 percent of the city’s inhabitants live in informal settlements. Given urban populations in Sub-Saharan Africa are expected to triple by 2050, it was vital for the Zambian government to document the influx of people now, before the situation becomes unmanageable.

“The local government spoke with the IGC, who approached us to help them out with providing detailed maps to support their work,” Wilson, the regional director of Ordnance Survey in Africa, said.

What is remarkable about OS's work in Zambia is that the team didn’t have to travel. Instead, the deployment happened exclusively in its headquarters in Southampton, the UK.

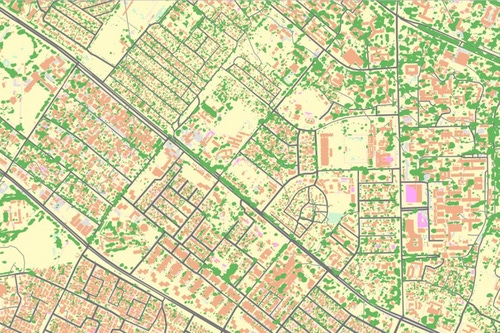

“We had access to high-resolution aerial imagery the land's authority provided us with. We were able to utilize that to create a workflow in Southampton, with our data scientists, architects, business analysts working on this project without any direct trips to Zambia,” Tabor, OS’s principal consultant, explained.

“We're used to manually capturing and maintaining data and we've done that for over 200 years – however, this capability is 90 percent more efficient than using traditional methods whereby an operator would be manually capturing every single building.”

Ordnance Survey used an automated system to create a 420km2 detailed base map in just 10 percent of the time it would take if done manually. Mapping at scale used to be costly and time-consuming, Wilson said. Now, however, the process is far more efficient, with other nations taking note.

“We're getting a lot of enquirers about doing this elsewhere, and there [are] some common themes that we see emerging, particularly across Africa, around managing informal settlements and mitigating risks to delivering public services in those areas,” he said.

“Sustainable urbanization is a big subject in the commonwealth, many countries are looking at that and they know maps are essential to plan urban developments.”

But it’s not just house building that the data can help with – but pandemic planning as well. Wilson told AI Business that the detailed mapping information they secured can be used to work out what responses are needed, and where.

He also suggested that detailed mapping can support nations in monitoring their sustainability ambitions. With COP26 fast approaching, and the truly sobering assessment of the Earth’s future in a recent UN report, spatial data could emerge as a tool we need to combat growing climate issues.

Nations that use this data to monitor climate change could create detailed surface models to manage and understand the impacts of flooding, Tabor said.

Other use cases are constantly emerging: once Zambia completes its upcoming census, government agencies can enrich the spatial dataset with the number of occupants, the location's proximity to hospitals, sanitation, and drinking water.

“For this particular use case, we captured all buildings over 12 square meters,” Tabor said.

“All sealed surfaces, natural surfaces, roads, grass, vegetation that had a canopy on it, and water features. That specification can be configurable and the expertise in our team helps the customer to decide what the use case is and whether the input data – be it satellite, drone, or aerial imagery – is appropriate for the end use case.”

Data ownership and licenses

Who owns the data OS collects? The data is available on a license which then enables customers to use it, Wilson explained.

“We always try and ensure that the data is available and accessible for whatever purpose it's deemed to support.”

In this deployment, the data was made accessible to the public sector in Lusaka, with a licensing mechanism provided.

“It can be used by the entirety of the local government to build applications to problems on the ground and we see it being used to support a range of new issues the Zambian government is trying to solve.”

Validation and extension: what’s next?

With use cases explored and licenses secured – what’s next for this project?

The deployment is likely to be extended to other nations, particularly those who haven’t updated their maps in decades.

Tabor revealed that some Commonwealth countries last updated their maps over 40 years ago, something that would have been done by the Director of OC Surveys. That office ceased to exist in 1983 – and today’s OS team can provide an opportunity to help governments secure helpful data, and get a return on their investment.

For Wilson, the project brings validation. He told AI Business that during 35 years he’s been in the industry, he was often frustrated that the power of maps and spatial data hasn’t been recognized by everyday citizens.

“The average person in the street would think of a paper map – this allows us to raise the profile of the role that spatial data plays in everybody's lives.”

“Research we did in the UK a few years ago showed that we interact with OS data in some shape or form 42 times a day on average. Whether it's ordering groceries online, receiving your power, having your waste collected – all these things that we take for granted in our everyday lives, our data is playing a role in the efficient enablement of those public services,” Wilson said, adding, “There's so much more that can and will be done with spatial data.”

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like

.jpg?width=700&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)

.jpg?width=700&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)

.jpg?width=700&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)

.jpg?width=300&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)

.jpg?width=300&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)