Origins of the current chip supply chain crisis, and potential remedies

The world might be getting closer to the end of this pandemic, but there is no sign of the great chip shortage subsiding.

The supply chain disruption made especially dire headlines for the automotive industry.

GM expects it to wipe between $1.5 billion and $2 billion from its operating profit this year, while earnings at Ford could be down anywhere from $1 billion to $2.5 billion.

Employees at many assembly points across the world have been put on ice until the chip supply improves.

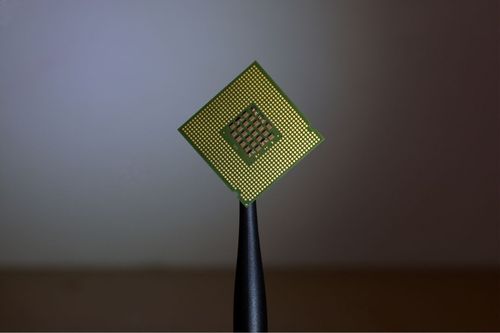

Unfortunately, the predicament has no quick answers. Producing microprocessors is highly time intensive: by some estimates it can take 11-13 weeks to meld seven, ten or 14 nanometer chips, the brackets into which most modern chipsets fall.

Lead times were extended for around three-quarters of semiconductor output in February 2021, according to IHS Markit, with around 11 percent delayed for more than 10 weeks.

Chuck Robbins, chief executive of networking hardware producer Cisco, told the BBC he expected the crunch to last at least until October.

No less pessimistic were TSMC’s chief executive C.C. Wei and Intel’s Pat Gelsinger.

Both are working to deliver new US-based chip fabrication capacity, but this won’t be ready until 2023 at the earliest.

There is also a conundrum to resolve: new ‘fabs’ will need enough semiconductor parts to operate.

Of course, businesses that provide goods and services to semiconductor makers are reaping the benefits.

On April 21, Dutch chip-making equipment supplier ASML said it expected annual revenues to come in 30 percent higher than in 2020, with projected 49 percent gross margins for the second quarter.

ASML’s offering includes lithography machines which imprint minute circuit patterns onto silicon wafers, using light projection templates.

The company expanded its customized lithography systems for owners of mature fab installations in the early 2000s – and it was this division that created most of the extra revenue.

For national policymakers, the lesson is that chip manufacturing can no longer be left to global market forces.

In a world where advanced silicon powers everything from military fighter jets to medical equipment, a semiconductor shortage is not merely an inconvenience.

It’s a potential national health and security crisis.

US President Biden on chip shortage

US President Joe Biden has committed $50 billion to enhancing domestic chip manufacturing capacity but will be expected to provide more.

Even more pressing is his executive order to resolve gaps in the domestic supply chain.

With unemployment in the US remaining high, in part due to factory shutdowns, the crisis is serving a stern test of Biden’s economic mettle. Intel is among those to have answered the President’s call, having pledged extra chips for American car plants within the next six-to-nine months, according to Reuters.

What caused the 2021 chip shortage

Fabless chip models may have done wonders for innovation and competitiveness, but the concentration of manufacturing in East Asia – home to almost 80 percent of chip foundries and assembly points, according to the Semiconductor Industry Association – means there’s a sharper brake on capacity when conditions get tough.

Fabs in the US were responsible for 12.5 percent of global chip manufacturing capacity in 2020, down from a far healthier 37 percent share in 1990.

And yet, the US-based chip vendors control almost half of global semiconductor sales, having accounted for 47 percent in 2019. East Asia’s formidable supply engine fell completely out of sync during the pandemic.

When the virus spread across the Chinese mainland in early 2020, it forced shutdowns at most of the region’s electronics factories.

Fewer items needing chips were being produced, so East Asian foundries responded by slashing output.

Western chip purchases began to fall in anticipation of the pandemic only for demand to then spike when other countries followed China into lockdown.

Stay-at-home workers suddenly needed new PCs, keyboards, and headsets. Families bought new game consoles.

Then, there were completely unexpected consumer behaviors. Soaring cryptocurrency values incentivized countless speculators to mine tokens using hi-end graphics processing units, which began selling out in droves.

While the crisis has affected the latest generation of game consoles and smartphones, the consumer electronics sector, on average, stockpiled more than automotive producers. In supply chains, there’s a delicate trade-off between just-in-time inventory management and building stock for contingencies.

Car chip shortage - when will it end?

It appears most automakers got caught on the wrong side of the equation.

Car makers that slashed chip orders when demand for new vehicles fell in the initial stages of the pandemic were then unable to locate fresh stock in sufficient quantities. Fabs running at full tilt can do little to help, as they already have extensive backlogs to service.

There’s a high price to pay for miscalculation at such a scale.

Automotive revenues this year could plunge by as much as $60.6 billion due to the shortages, according to consulting firm AlixPartners.

In the midst of the crisis, it has also become clear that semiconductors underpin the modern car’s value proposition.

Automakers purchase around $37bn worth of chips each year globally, with around 40% of the cost in producing new car models going toward electronics-driven systems, according to some reports.

The average modern car is thought to execute 100 million lines of software code. Core functions like braking and power-steering which historically relied on hydraulics are now augmented by semiconductors.

One of the few automakers to stockpile enough chips to cope in the crisis was Toyota, but then the company has already been in this position once before, following the Tohoku tsunami in 2011.

The crunch in Toyota’s local chip supply chain forced the company to re-examine its strategy. Ahead of the current shortage, it had reportedly built a stockpile for around one-to-four months, putting it well ahead of many of its competitors.

As the industry veers toward electric and autonomous vehicles, the amount of chips carmakers need is likely to increase.

For Toyota’s rivals, better contingency planning and supply chain visibility will surely have moved toward the top of the agenda.

Just one boat

One of the most surreal events of recent times was the shipwreck of hulking container Ever Given, which slammed into the side of one of the world’s busiest shipping canals in March.

Thankfully no one was injured, but it was almost a week before the vessel was finally dislodged from the Suez Canal by tugboats and dredgers.

By that point, many freight containers had already embarked on a nine-day detour toward South Africa’s Cape of Good Hope.

In the following weeks, Shoei Kisen Kaisha, the owner of Ever Given, refused to pony up the reported $900m compensation, and the vessel was impounded by Egyptian authorities.

The debacle was but the latest in a string of supply chain disruptions that have exacerbated the ongoing chip shortage. A cold snap in the US state of Texas interrupted semiconductor deliveries and was followed by a blaze at a chip factory owned by Japan’s Renesas Electronics.

Nikkei Asia has predicted that automakers will be forced to pare back 2.4 million vehicles, or around 3%, from anticipated output this year as a result of the disruptions. The situation is expected to deteriorate even further due to water shortages affecting Taiwan’s west coast.

Incidentally, automation was cited as one of the contributing factors in the 400-meter long Ever Green’s crash.

The shipping industry has increasingly opted for computerized systems to keep down crew numbers. This has enabled shipyards to limit costs despite expanding the size of many newly-built container ships.

With the autonomous shipping market expected to grow from $90 billion at present to above $130 billion by 2030, the accident is a stark reminder that adequate manual resources must be deployed to back maritime AI systems.

Doing so will only become more crucial as AI-based systems become more advanced. In the same month that Ever Green was shipwrecked, IBM and marine research organization Promare announced they would trial an AI-driven navigation system aboard a transatlantic autonomous ship called The Mayflower.

At the time of this eBook going to press, the ship’s autonomous journey had been derailed by a fault, although project managers hoped it could be assessed and repaired.

To read more about how AI can help predict and prevent disruption in the supply chain, check out our eBook: ‘AI in supply chains: Helping businesses respond to change’

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like

.jpg?width=700&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)

.jpg?width=700&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)

.jpg?width=700&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)

.jpg?width=300&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)

.jpg?width=300&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)

.jpg?width=300&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)

.jpg?width=300&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)

.jpg?width=300&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)