Intel, Ubotica, and the European Space Agency launch “first AI-powered satellite”

Bringing Photoshop to space

Bringing Photoshop to space

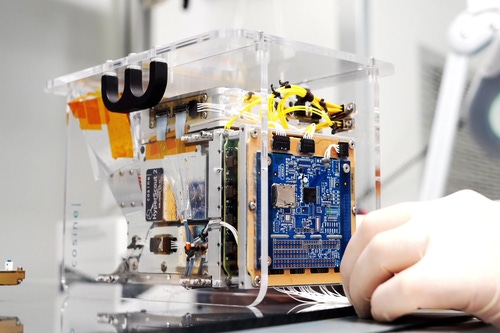

Chipmaker Intel, computer vision startup Ubotica, and the European Space Agency have come together to launch a satellite into space.

They claim the PhiSat-1 is the first AI-powered satellite, using on-board computing and artificial intelligence to improve how it photographs the world.

The cubesat was launched in September aboard an Arianespace Vega rocket, after delays caused by COVID-19 and poor weather.

No need for the cloud

Satellite imagery has always had to contend with the fact that around 70 percent of the time there’s something in the way of a clear shot of the ground – clouds. Traditionally, satellites waste a huge amount of bandwidth, storage, and end-user time with images of clouds.

“The capability that sensors have to produce data increases by a factor of 100 every generation, while our capabilities to download data are increasing, but only by a factor of three, four, five per generation,” Gianluca Furano, data systems and onboard computing lead at the European Space Agency, explained.

The PhiSat-1 hopes to improve the situation by using AI to filter out cloud-covered images at the device level. In a three week test, the satellite beamed down every image it took across the visible, near-infrared, and thermal-infrared spectrums, but noted which images it would have discarded.

After checking the results, the ESA are now happy to proclaim the project a success. “We have just entered the history of space," Max Pastena, PhiSat officer at the ESA, said.

But before the team could send the satellite into space, it first had to ensure that the hardware would be able to cope. Normally, satellite processors are developed over several years to be radiation-hardened – but this means that they are often years or decades behind consumer equipment, and not suited for modern AI algorithms.

The group wanted to use Intel’s Movidius Myriad 2 Vision Processing Unit (VPU), but it was designed with ground-based applications in mind. To see if it could cope in space, the ESA took the chip to a particle accelerator at CERN and blasted it with radiation for 36 hours.

The chip survived, and passed two follow-up tests. This meant that the team now had a chip capable of AI, as well as of running multiple applications.

“Rather than having dedicated hardware in a satellite that does one thing, it’s possible to switch networks in and out,” Jonathan Byrne, head of the Intel Movidius technology office, said.

In addition to proving the viability of cloud detection, PhiSat-1 will help monitor polar ice and soil moisture, while also testing inter-satellite communication systems with a sister device, ahead of potentially building a network of federated satellites.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like

.jpg?width=700&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)

.jpg?width=700&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)

.jpg?width=700&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)

.jpg?width=300&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)

.jpg?width=300&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)

.jpg?width=300&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)

.jpg?width=300&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)

.jpg?width=300&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)